When discussing the reliability of the Bible, the question of the Canon is often raised. The Canon of Scripture is the list of the books that belong in the Bible1. Generally, among Christians the formation of the Canon is rarely explored, and Muslims often use this topic to leverage their view that the Jewish and Christian Scriptures have been corrupted. How do we know that the 66 books of the Bible are the correct ones while there are so many other writings that could have made it into the Canon?

Among Muslims in Turkey, for example, it is widely believed that the four Gospels were chosen at the council of Nicaea, as “the bishops shook the table with hundreds of Gospels on it. Most of the books fell off, only four remained, and so these were accepted as the true Gospels.”2

While this claim appears to mirror in part the process of the standardisation of the Quran by Uthman (see Bukhari 6.61.510), more sophisticated and credible objections make reference to the Apocrypha and Gnostic writings, as well as the claimed ambiguity of inclusion of books like Hebrews, James or Revelation in the New Testament by prominent Christians in church history, such as Martin Luther. For Muslims, this doubt over the canonisation of the Bible suggests its corruption3.

The Apocrypha refers largely to a collection of books mostly written down4. They are not included in modern Protestant translations. Historically, while there were some who saw them as part of the Bible Canon, through the ages the majority have seen them simply as the writings of “godly men”, useful for “the advancement and furtherance of the knowledge of history and for the instruction of godly manners”5. In support of not recognising the Apocrypha as Scripture is the fact that none of the works of the Apocrypha claim to be6 inspired, and that the Jewish people from whom they originated did not recognise them as inspired by God. They were never quoted by Jesus or the apostles, and they contradict the teaching of the Bible7.

Aside from the Apocrypha, there are other texts written from the 2nd Century that give accounts of Jesus, his words, or details of the apostles, known as the New Testament apocrypha8. These were texts either known by or referred to by early Christians or written by those who followed the Gnostic heresy. However, the early church rejected these as not being inspired by God. They often included bizarre things. The Gospel of Peter depicts Jesus after His resurrection as being so tall that his head reached into the heavens, while a cross follows Him from the tomb and speaks9.

The Church Father Origen lists Thomas, for example, as heterodox10, and Bishop Eusebius says of Thomas that it is the “fictions of heretics”11. The text of the book shows how contrary it is to the teaching of Jesus, with Thomas quoting Jesus saying things like, “make Mary leave us, for females don't deserve life” and “every woman who makes herself a male will enter the kingdom of Heaven12.

Martin Luther’s famous objection to the letter of James as “an epistle of straw” is a common example raised by Muslims, who either struggle to understand the canonisation of the Bible or argue against the Bible. His difficulty with James is easily understood in the context in which he was writing, given the Catholic Church’s insistence on the place of indulgences (works) in the place of salvation. Even Luther, however, included James in his own canon, albeit with a secondary status13. The issue Luther had with the letter, based largely around James 2:24, is easily resolved when we understand that James is using the word “justified” (or “considered righteous” NIVUK) in a different way to how Paul uses it in his own letters. While Paul uses the term to describe the declaration of the believer as righteous, James is making the point that if someone has been declared righteous or forgiven, you will see the proof, or “justification” of the fact in their lives, something that Paul frequently states14.

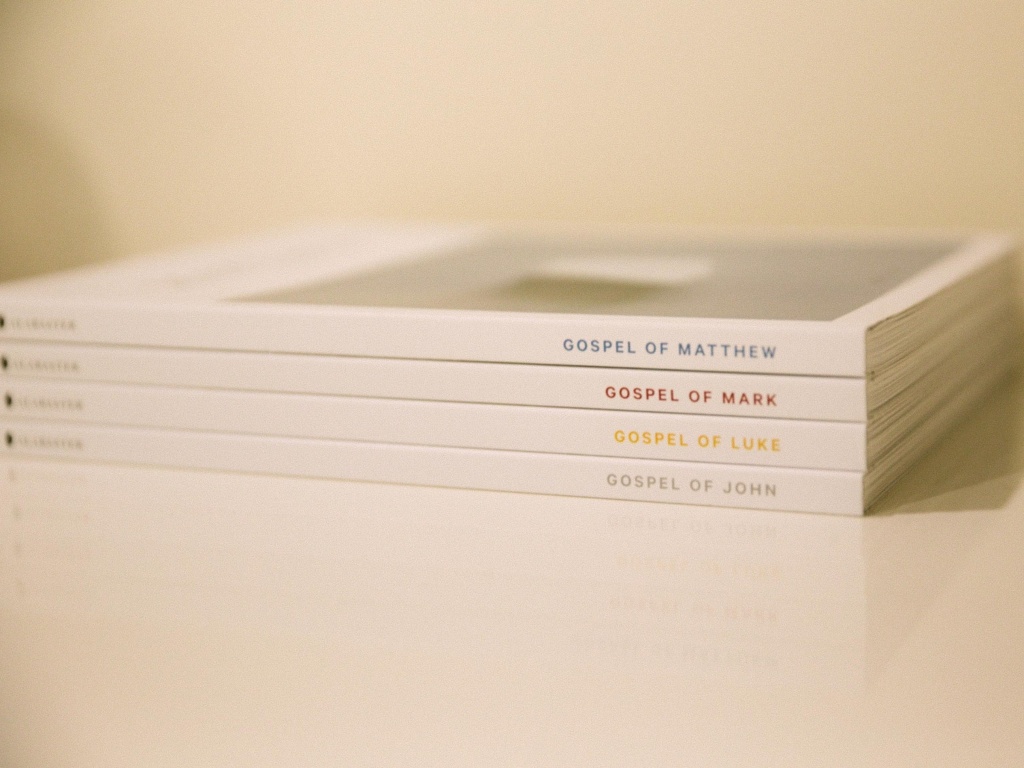

One approach to coming to a place where we can be sure we have the correct books is to look at the history of the early church and see the way that different groups of Christians in different places and at different times came to the same conclusions15. When it comes to the New Testament, we could point to the 397 AD Council of Carthage16 as a key council that discussed the question of the canon17 and ratified the one proposed by Athanasius. However, a text even as early as 170AD titled the Muratorian Canon18 lists a canon remarkably close to the books included in the New Testament. The books of the New Testament are also well evidenced in the writings of the Church Fathers, including Clement (95AD), Ignatius (107AD) and Polycarp (110AD)19.

However, when it comes to the Canon it is important to remember that while we can point to individuals or councils that have arrived at the 39 books of the Old Testament and the 27 books of the New Testament, or something close to it, no one actually has the authority to declare a book in or out of the Canon; we can only recognise each part as something being inspired by God guided by his Spirit. Books inspired by God are by their nature self-authenticating20. Bruce Metzger notes “Neither individuals nor councils created the Canon; instead, they came to recognize and acknowledge the self-authenticating quality of these writings, which imposed themselves as canonical upon the church.”21

This approach to the Canon is essentially theological rather than historical, and serves as a great response to our Muslim friends when questions of Canon arise. It starts with the premise that God has chosen to reveal himself through the Spirit-inspired writings of those he has chosen. In response with the help of his Spirit, his church has been able to discern which books have been inspired by God.22 Two key verses that give a foundation for this are John 16:13, where Jesus promises that the Spirit will guide his disciples into truth, and then John 10:4 where Jesus points out that “his sheep follow him because they know his voice.” This approach can be helpful when addressing issues like the authorship of Hebrews, where no one knows for sure who wrote it.

Underpinning this approach is the belief in the faithfulness and providence of God. This argument is similar to the approach laid out in “God the all-powerful and most loving”. If God is ultimately caring of us, faithful, and wants us to know what he has revealed, then why would he allow anything other than the books he wanted to take their final place in his revelation? We trust him to protect his word, and we trust him to lovingly ensure we have all the writings that he has inspired.

Answering the question from the historical perspective is possible but far from easy, and requires a lot of reading and research. It is not surprising that attacks against Scripture can be made leveraging this topic. Responding with the theological basis for our trust in the 66 books of the Bible is much simpler and closer to the way our Muslim friends understand the integrity of the Quran. (However, see “Is the Quran Reliable” for further discussion.)

As mentioned above, rooting this argument in the words of Jesus is a good place to start.

It can also be useful to ask a Muslim friend, if they mention a specific apocryphal text, if they have prayerfully read the text in question themselves, while at the same time challenging them to read a Gospel or the whole New Testament prayerfully. As Jesus said in John 7:17, “Anyone who chooses to do the will of God will find out whether my teaching comes from God or whether I speak on my own.”

Trust that Jesus is able to reveal himself to your friend through Scripture.