Muslims are instructed to believe in the books revealed before Islam began, the Tawrat (Torah), Zabur (Psalms) and Injil (New Testament) (see Quran 2.4 and Quran 4.136). However, even though the Quran affirms the reliability of the Jewish and Christian scriptures at the time of Muhammed, Muslims now claim that the Bible has become corrupted. This is largely due to the fact that the Bible and Qur’an make very different claims about: the identity of Jesus, whether Jesus died on the cross and the coming of Muhammed as the final Prophet.

This presents Muslims with a dilemma; is it possible to obediently believe in the ‘previous scriptures’ when they contradict key Qur’anic teachings? The Gospel of Barnabas1, however, seems to offer Muslims the ability to anchor the Quran’s claims about Jesus and Muhammed in the 1st century.

The identity of the Biblical Jesus is contradicted in the opening paragraph; Jesus is not presented as divine nor the Son of God, but as simply a prophet (See chapter 53). The Gospel of Barnabas also corroborates the Quran’s claim in Quran 4.157 (cf. Quran 3.55) that Jesus did not die on the cross, it was only made to appear so, while Jesus was raised up to Allah . Chapter 217 of the manuscript claims it was Judas who endured the passion; clothed in a purple robe, mocked as king, received a crown of thorns, crucified, crying out Jesus’ final words, “God, why have you forsaken me?”. According to Barnabas, Judas was then buried in Joseph’s tomb. From a Christian perspective, these claims remove the foundational teaching that Jesus in his suffering and death provided salvation.

Many Muslims are encouraged that the Gospel of Barnabas also mentions Muhammed by name, presenting him as the one who would follow Jesus as the messenger and prophet of God. This provides Muslims with a great opportunity to refute the message of the New Testament. Adam is said to have seen the Shahada (“There is only one God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God”) written in mid-air above the gates of paradise (Chapter 39 & 41). In this gospel Jesus becomes the “voice of one crying in the wilderness” (chapter 42) and “unworthy to untie Muhammed’s shoelaces” (chapter 44), therefore making Muhammad the “Messiah”.

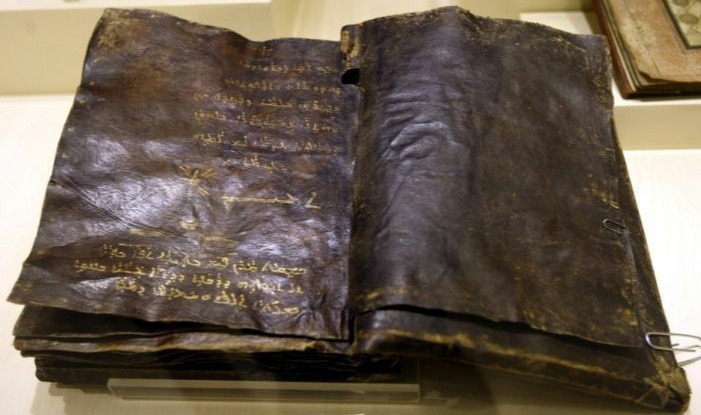

Even though some Muslim scholars hold the gospel to be genuine without evidence, including Yusuf Ali in his introduction to his translation of the Quran2, the majority of experts, however, recognise that the document is a forgery composed late middle-age or early modern period, concluding that it was probably written in either Spain or Italy in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. The earliest surviving manuscript is from the 18th Century.

It is not a surprise that many Muslims, as mentioned above, love to hold to the authenticity of the Gospel of Barnabas. However, just stating what the document says without giving historical evidence showing it was written early does not make it authentic. When Muslim publishing houses started publishing an English translation of the book from 1907 by Lonsdale and Laura Ragg, they chose to omit their original introduction, in which they gave their basic reasons they believed it to be a forgery, instead claiming it to be authentic.

While it appears to offer a “too good be true” resource for Muslims, it actually contains things that contradict the Quran. Quran 2.29 states the existence of seven heavens, while according to Barnabas there are nine (178) The Quran approves of polygamy, whereas the Gospel of Barnabas does not tolerate it (115). The Quran condemns eating pork, but Barnabas repeats Jesus’ words, making all foods clean (32). There are also other simple mistakes that contradict the Bible. For example, in Chapter 82 states that the Jubilee is a centenary event when according to the Bible it is celebrated every 50 years. Moreover, there are references that show medieval authorship, such as references to Dante’s view of hell (see chapters 60, 78, 106 & 217).

A further error in the Gospel of Barnabas is the claim that Jesus is “the Christ” (introduction and chapter 6), but not “the Messiah” (chapter 42). The author was apparently unaware that Messiah and Christ carry the same meaning in Hebrew and Greek respectively.

There are also historical errors such as the claim that Jesus “sailed to his city of Nazareth” (Chapter 20). This would be difficult considering that Nazareth was 14km from the sea of Galilee located hundreds of meters above sea level . Contrasting the textual evidence we have for the New Testament, it is ironic that on the one hand Muslims are quick to appeal to a false “Barnabas”, while on the other dismissing a New Testament clearly authenticated by archaeological evidence dating hundreds of years before Muhammad. In view of Muslims claiming that the Bible contains contradictions, it is telling that the gospel of Barnabas is not rejected on the same grounds.

Some Muslims will claim that the presence of a “Gospel of Barnabas” on a 6th Century and a 7th Century list of apocryphal works, and the existence of other works with a similar title, (e.g., the 2nd Century “Epistle of Barnabas” or the 5th Century “Acts of Barnabas”) shows that the gospel in question is authentic.

However, prominent Muslim scholars recognise that it was written in the fifteenth century by some unknown Muslim author to help support the Quranic view of Jesus.3

Shabir Ali, a prominent Muslim apologist states: “I hesitate to use it as an authentic account because … for many hundreds of years this gospel was not seen anywhere and then suddenly turned up in the Middle Ages, so because of that break in continuity [in the chain of authority] … I hesitate to use it as an authentic account of the life of Jesus.”4

Where our Gospel friends make mention of the Gospel of Barnabas, while it is worth pointing out the fact it is a forgery, it is also worth exploring with them the importance of historical evidence. Do they just believe what they are told, or are they willing to investigate for themselves? It is good to express our confidence in the historical reliability of the Old and New Testament scriptures.

When we understand the blatant way that the Gospel of Barnabas makes so much of Jesus’ ‘Passion’ to be the experience of Judas, we may feel a sense of sadness and even anger. However, it is worth remembering that for our Muslim friends the idea of God allowing Jesus to suffer such a shameful and humiliating death is hard to understand, and one that for them will seem so much more fitting for Judas. It may be worth taking time to read through the sections titled “Defending the Incarnation” and “Defending the Cross” to get some orientation in this.